The ‘‘quirkiness’’ of Oamaru’s Victorian precinct has drawn in its next resident artist, with Buggyrobot man Martin Horspool and his partner Wendy Jones making the move from Auckland earlier this year. The pair sat down with Ashley Smyth to talk about robot building, following signs and their new gallery.

Martin ‘‘Robot Man’’ Horspool is a big believer in signs.

When the Welsh-born artist and English partner Wendy Jones both brought home the same advertisement for a printing job vacancy in Auckland 25 years ago, they took it as a sign they should move from the United Kingdom to New Zealand.

They had never been before, but ‘‘used to read books on it’’.

And when they saw a metal badge on the back of a friend’s Bedford truck during a visit to Oamaru in March this year, with ‘‘Llangollen Canal’’ written on it, it was another sign — Llangollen being Horspool’s home town — and they decided to move again.

‘‘We always believe in the signs, and when it feels right,’’ Miss Jones said.

Llangollen is about 16km from the more widely-recognised Wrexham, in the limelight recently due to the purchase of its football team by actors Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney, and the resulting documentary series Welcome to Wrexham.

‘‘Wrexham has never ever been on any glamour map, as you can tell,’’ Horspool said.

‘‘We’re from a more beautiful place . . . not too dissimilar to Oamaru, but smaller.’’

Horspool, who had always been an artist ‘‘on my days off’’, worked as an off-set printer for 42 years — until about six weeks ago, while Miss Jones had been a regional manager for The Body Shop before being made redundant in February.

Selling their Auckland home and moving to Oamaru meant he could now concentrate on his artwork full-time, and the couple have this week opened the doors on their new Harbour St gallery and studio.

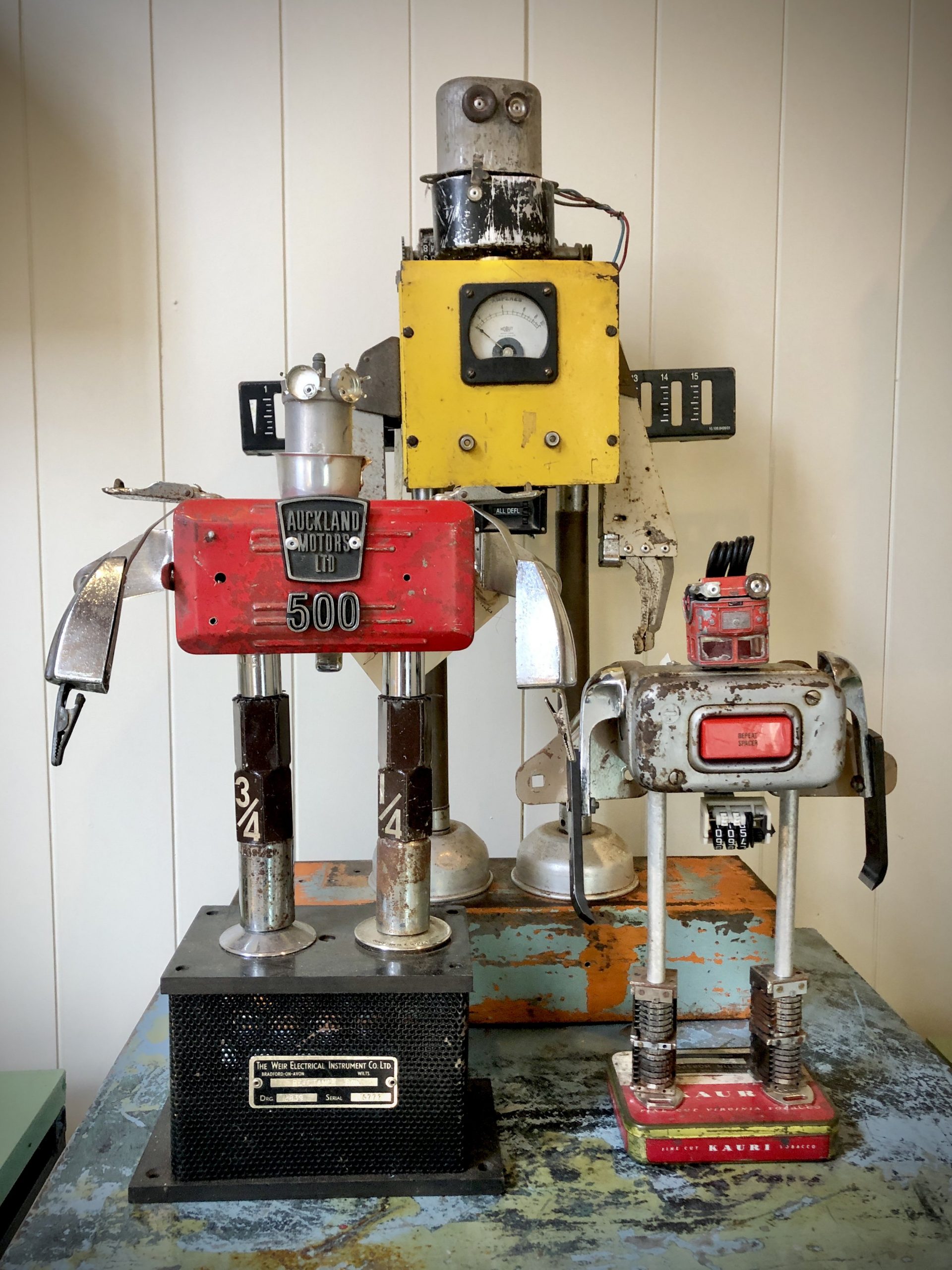

Horspool’s robotic era began about 15 years ago, after he saw some art made from household items such as kitchen utensils and picture hooks.

‘‘I thought, that’s really clever . . .I realised I could transform my drawings into real objects. Instead of, like, two-dimensional sketches of insects or robots, I could actually build them.’’

The response to his work, he said, was always positive.

‘‘It’s always a ‘wow’.’’

Children loved the robots because, well, children like robots; and older fans of Horspool’s work enjoyed it because they recognised the parts, which tended to be vintage objects, he said.

The time to build a robot was about two to three days, but collecting the components ‘‘takes a lifetime’’. Pieces were bolted, screwed or riveted together, but not welded.

‘‘It usually starts off with a body — maybe an electronic switchbox, that’s probably 60-70 years old.’’

The rest was made by ‘‘cherry-picking’’ from boxes containing potential eyes, noses, heads, and hair, to fit an image he had in mind.

“I see it as a three-dimensional jigsaw, and I’ve got the picture on the box, which is inside my head, and the jigsaw pieces are all my bits and pieces of retro, collectable junk that I’ve got.’’

He was also sometimes asked by families whose loved ones had died to build a robot memento from their old tools.

‘‘So Martin will get them to tell him about the person, then you’ll see a photo of them, and you’ll go and cherry-pick what you think you’d like, from their old belongings . . . and when they see it, they all start crying. It’s so emotional,’’ Miss Jones said.

‘‘That’s the thing with the robots, people just warm to them, and I imagine them being alive in a way.’’

Horspool was also producing a new series of paintings using mostly Resene acrylic testpots on recycled plywood.

Oamaru’s Victorian precinct was mainly what enticed the couple to move here.

After finding themselves enjoying the peace of the Auckland lockdowns, they struggled to return to the normality of work and commuting, and then Miss Jones lost her job.

‘‘In March, we said let’s go for a trip to the South Island . . . open-minded and just work out what the future is,’’ she said.

‘‘Then on that trip we came across Oamaru and fell in love. We just sat on the pavement outside and I said to Martin, ‘oh my gosh, I could live here. Martin says, ‘good, so could I’.’’

It was the ‘‘quirkiness’’ of the town, the architecture and the people, the couple loved. It was not frowned upon to be creative, he said.

The dream was to set up business in Harbour St, but the couple never expected it would happen so quickly, and after a slight refit and freshening up of the former Nana Bangles premises, they were excited to be opening Buggyrobot Gallery.

‘‘We’re completely blown away by the actual building that we’re in. It’s absolutely bang-on perfect,’’ Horspool said.

It would be the first time he had a permanent setup, and likened it to having a full-time exhibition.

In Auckland he would work away in a studio at the bottom of his garden, and only showcase his work every couple of years.

A sellout exhibition in New York about five years ago was the ‘‘absolute ultimate’’ of his career so far.

“It was nuts.’’

Adding to their adventure, the pair had also been filmed for a new television series, called Country House Hunters, which is due to screen in January.

They were ‘‘right time, right place’’ for the show, which is based around people moving from a city to the country. The couple think they appealed because their move was ‘‘completely on a whim’’.

And so far, following the signs was paying dividends.

Horspool said it was nice to be out of the city, and doing what he was passionate about.

‘‘I don’t have to do my normal getting up at 3.40am to go to work for 4.30am, and then coming back home after a 12-hour shift through Auckland traffic, all that stuff. So it’s quite nice, it’s great.’’